Jeanne de Clisson

Text & artwork by Natasza Rogozinska

Natasza Rogozinska is a trained fashion designer, but she rather focuses on illustration and graphic design. Her works have been showcased in Vogue Poland, i-D Magazine, Kaltblut Magazine, Waste Not exhibition at the IFS Somerset House, London, and others. Natasza is now working on a master project, reviving stories about forgotten women from general history, myths, and legends. She combines traditional and analog techniques such as embroidery and linocut with digital art – to create a feminine chronicle of these forgotten stories.

We have already published one of her articles here. Today we proudly present her text and graphics.

If you would like to read more of her stories and watch more of her work, you can find them (external link) here.

When you hear about a brave French woman named Jeanne, first character that comes to mind is obviously Jeanne d’Arc. However, she was not the only battle-hardened Jeanne to tread the French lands. In the year 1300 Jeanne de Belleville – who, a mere 40 years later, would abandon noble manor and luxury – ws born into a wealthy family. Why did she forsake the aristocratic path, you may ask? The answer can be encapsulated in just one word: revenge.

Jeanne de Belleville was born as the daughter of French aristocrats, wealthy and highly respected. Her father, however, dies quickly – and Jeanne inherits the dominion over lands in Belleville and Montaigu as a result of this tragedy. As a 12-year-old (and this was apparently a suspicious age anyway, even for the Middle Ages) she enters into her first marriage with 19-year- old Geoffrey de Châteaubriant VIII, to whom she bears two children. In 1326, Geoffrey kicks the bucket and Jeanne prepares to marry Guy de Penthièvre – the marriage is, however, questioned by a certain (quarrelsome by nature) French family called the de Blois. Their exaggerated lament causes Pope John XXII to annul the scandalous marriage for political reasons, obviously. Guy then marries Marie de Blois – and dies shortly thereafter. Coincidence? Might be.

Meanwhile, Jeanne marries (without papal interference) Olivier IV de Clisson, a mighty Breton, who owned a castle in Clisson, an estate in Nantes and lands in Blain. Adding Jeanne’s lands to it suddenly it appears that the Clissons are becoming a true feudal power in Brittany. Olivier and Jeanne are well-respected and has a good reputation among Breton society. The de Clisson family quickly expands and now consists of not only Jeanne and Olivier, but also of their five children – Isabeau, Maurice, Olivier, Guillame and Jeanne. What the de Clisson family does not know yet is that they are on the eve of a succession war in Brittany – this will change their fate forever.

To understand the intricacies of this (one of many, as we all know) French-English argument, it should be mentioned that in the 14th century Brittany was a province ruled by a duke. The Bretons had a strong sense of Breton identity – even though their loyalties were divided between two kings – Philip VI of France and Edward III of England, the Bretons were always loyal to the duke above all. One can only imagine the cliffhanger that ensued when the Duke of Brittany, Jean III le Bon, dies childless in 1341. The war for the Breton succession is set in motion, with each side fielding its own player – in the blue corner you can see John de Montfort, backed by Edward III of England and in the red corner you can see Charles de Blois, sympathetic to Philip VI of France.

It was therefore necessary to take sides, to bet a few pennies on someone. Olivier de Clisson decides to support his childhood friend, Charles de Blois – who, after all, comes from the very same family of whistleblowers that denounced Jeanne and Guy de Penthièvre before the Pope. In 1343, Olivier and Hervé VII de Léon, as military commanders, defend the city of Vannes against attacks by the English – who eventually succeed after four attempts to force the city. Olivier and Hervé are taken into captivity, from which only Oliver emerges – exchanged for the English Ralph de Stafford and a suspiciously small sum of money. And that is when Charles de Blois stabs his childhood friend in the back – suggesting that Olivier surrendered Vannes to the English without a fight, what is more, since they exchanged him for such a small amount of money, he must have sold himself to the English. Treason!

In 1343, after the truce between England and France was officially signed, Olivier and fifteen other Breton and Norman noblemen are invited to a tournament to celebrate. However, there is no celebration foreseen for Olivier IV de Clisson – he is captured by his compatriots and taken to Paris – on charges of unthinkable treason. Jeanne, trying to save her husband, resorts to bribery – as a result of which the royal sergeant tries to delay Olivier’s trial. The truth comes out eventually and he gets arrested – as is Jeanne, who is not only accused of attempted bribery, but also of treason and disobedience. Finally, she runs away with the help of her eldest son, Olivier, as well as her squire and butler.

Meanwhile, on August 2nd, 1343, Olivier IV de Clisson finally stands trial – and is accused of conspiring and forming alliances with Edward III, an enemy of the French king and all of France. He is beheaded, and his head is taken to Nantes, where, impaled on a lance, it becomes a warning to others. This shocks the noblemen, because evidence of Olivier’s guilt is lacking, and moreover, desecrating the corpse and displaying it in public as a warning was the domain of the lowest class of slaughterers and criminals – not aristocrats.

Filled with fury and rage, Jeanne takes her two younger sons, Olivier and Guillame and heads to Nantes to show them their father’s head impaled on a lance and set on the city gates. She swears revenge to Charles de Blois and king Philip VI of France. She sells rest of the valuables, gather s400 loyal men and begins her crusade against France. She attacks the castle of Touffou, which was under the command of Galois de la Heuse, an officer of Charles de Blois. He allegedly recognized Jeanne and lets her in – after that her forces massacred the entire garrison, leaving only one wretch alive.

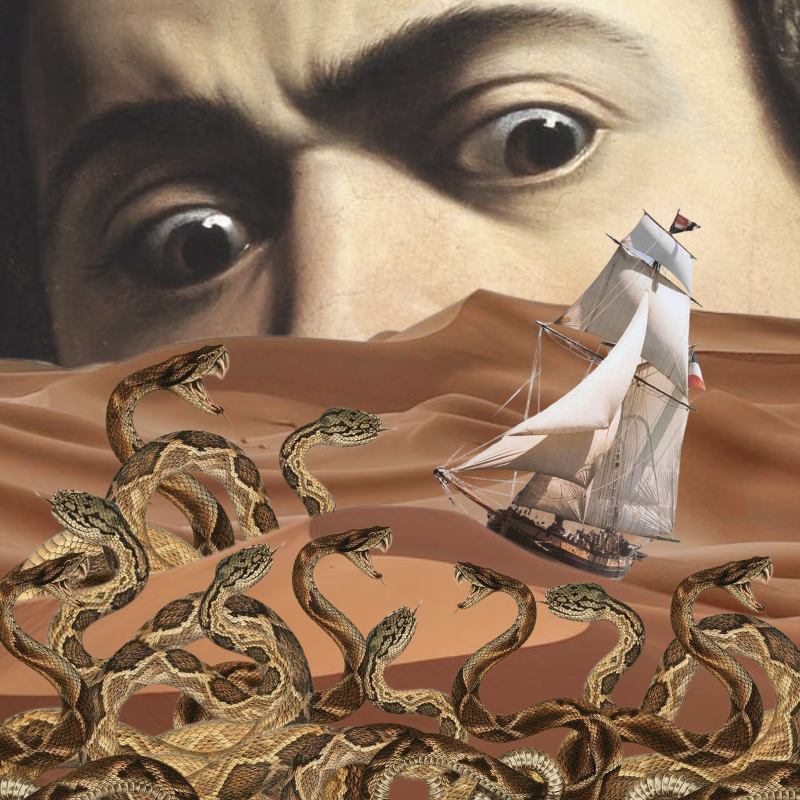

Soon after, with the help of the English king and Breton sympathizers, Jeanne organizes three warships, which are repainted black, their sails dyed blood red – and the flagship is christened with the name “My Vengeance.” Jeanne disguises herself as a pirate and goes to the sea with her Black Fleet. For the next 13 years, she hangs around the English Channel, spotting French merchant ships and attacking them without ruthlessness – always leaving one (un)lucky man alive to report to the French king that the Lioness of Brittany has caught up with them. And it was a tactic that can be described as guerrilla warfare at sea – disrupting the enemy’s logistics by attacking merchant ships, never military vessels.

In the end, however, the French manage to track down Jeanne and sink her flagship, so she drifts along with her sons for 5 days in troubled waters – as a result of this tragedy one of them, Guillame, dies. Jeanne and Olivier are eventually rescued by Jeanne’s allies, the de Montforts – and the Lioness of Brittany continues her pirate expeditions. In 1350, Jeanne marries for the last time – to Walter Bentley, closely related to King Edward III. They settled at Hennebont Castle and lived in relative peace for the next couple of years (not counting Walter’s little squabble with King Edward III over Jeanne’s estates). In December 1359 Walter dies, and a few weeks after him Jeanne – leaving behind a clear message: do not make baseless accusations of treason and do not desecrate the corpse – or the Black Fleet will catch up with you. Got it?